DETROIT — Nine years and five days ago, Javier Báez strode to the plate in the 13th inning of a tied game holding a pink bat. It was Mother’s Day in Chicago. The 2016 Cubs were about to take over the world. Báez got a 2-2 slider, connected and sent the ball screaming into the left-field seats for a walk-off home run. That was the day Báez introduced himself to Major League Baseball in grand fashion. That was the start of a free-swinging, swift-gloved kid’s ascent to stardom.

Flash ahead. After the World Series and the Gold Glove, after a trade to New York, a thumbs-down to Mets fans, Báez signed with the Detroit Tigers on a six-year, $140 million deal. This was his talent fulfilled, a contract that would secure his family generational wealth.

“Signing a player like Javy I think sends a message to the baseball world, to the fans, that the Tigers are here to compete,” Tigers CEO and chairman Chris Ilitch said after the deal was complete.

It started well. A little more than three years ago, Báez belted a ball to the right-field wall at Comerica Park that brought home the winning run on Opening Day. The crowd chanted his name. Javy. Javy. He stood on the field in dreary weather and talked of the journey ahead. “It’s not gonna be easy,” he said. “But it’s gonna be fun.”

Another fast forward. Last August, Báez walked into manager A.J. Hinch’s office at, of all places, Wrigley Field. His body was damaged and his spirit was beaten. His Tigers tenure had certainly not been easy. Little of it had been fun. His average was .184. The power that once made him so electric was sapped from his bat. Báez told Tigers officials he could not play. Eventually, the team recommended surgery to correct a right hip issue that had plagued him for longer than anybody knows.

Báez flew to Florida for the procedure and rehab. After years of boos and frustration, fans wondered whether the Tigers should simply eat the three years and $73 million left on a contract gone awry.

“Last year it was a hard decision to get surgery,” Báez said.

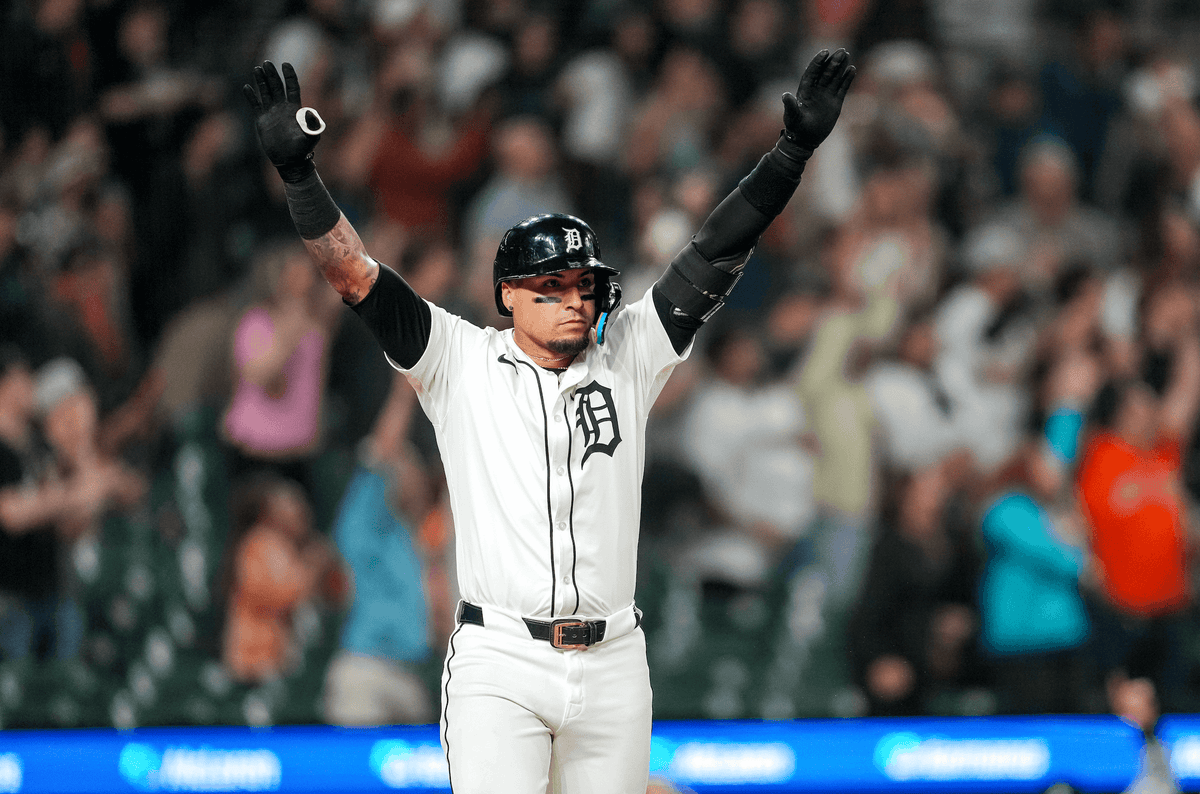

One last scene: Tuesday night in Detroit, Báez stood outside the third-base dugout, put his feet together and lifted his arms to the sky. He welcomed the cooler-dump teammates Justyn-Henry Malloy and Tomas Nido bestowed upon him. He smiled and embraced the chill while Gleyber Torres poured baby powder on his head. Báez hit two home runs in a 10-9, 11-inning victory against the Boston Red Sox. The first was a three-run shot in the sixth inning to give the Tigers a lead. The second was another three-run blast into the night to seal a remarkable victory.

“Honestly, I’m grateful to feel like this,” Báez said after it was all over.

The year is 2025. A Gold Glove infielder is playing center field. A player thought to be left by the wayside is hitting .319 with an .870 OPS.

In a game filled with numbers, statistical models and detailed projections, sometimes the unthinkable, the unfathomable, still happens.

Tuesday night down in the service level at Comerica Park, Hinch looked into the camera, shook his head and he tried to summon the right words.

“I am so happy for that guy,” Hinch said. “I don’t know if he’s gonna tell you how important it is to him. I don’t know if he’s gonna tell you how much it means to him. But I know it does (mean a lot), and our whole team explodes. Not just because we win, and not just how we win. But the fact that Javy’s right in the middle of it, it’s so awesome.”

Before this year, his age-32 season, Javier Báez had never played center field in the major leagues. He had dreamed of it. Desired it. Never fully gave up on the idea.

As a child in Puerto Rico, Báez grew up an outfielder. He enjoyed the chase, using his instincts to run balls down. By the time he was a high schooler in Florida, he moved to the infield. Scouts and others involved in the draft process, he said, recommended it. At first, he loathed playing on the dirt.

He mimicked fielding a ball, turning his head away.

“I hated ground balls,” he said. “I was scared.”

He got drafted in the first round, ninth overall. He grew into a dazzling utility player. He finally settled at shortstop and won a Gold Glove, sliding to his right, diving to his left, slapping down his patented, lightning-quick tags whenever he had the chance.

In three seasons with the Detroit Tigers, Báez had only appeared in the field at shortstop. But this spring, Hinch approached Báez about the idea of playing other positions. It started, seemingly, with third base. After three dismal years, it would be a way to keep Báez involved. This was also a clear acknowledgement that Báez’s days as the Tigers’ everyday shortstop were over.

“If I stay healthy, I’ll do whatever, man,” Báez said. “I can even catch if you need me.”

Said Hinch: “The fact we could have an open conversation about how he could do it, what was needed on this team, how we were different than that August date when he left us, it was pretty cool for a player who has been through as much as he has.”

By the middle point of camp, the Tigers were down two center fielders. Báez started getting reps in the outfield. It began with shagging balls and playing in back-field scrimmages. He borrowed a glove from minor-league teammate Bligh Madris while he waited for his own orders to arrive.

The Tigers lost Matt Vierling, Parker Meadows and Wenceel Pérez all by the end of spring training. They tried Ryan Kreidler, another converted infielder, in center field. They soon sent Kreidler down because of struggles at the plate.

The Tigers’ primary center fielder these days? Look no further than the 5-foot-11 athlete with tattoos down his arms. He’s roamed the grass with grace. At Angel Stadium, he leaped at the wall and brought back a home run, playing it off like it was no big deal.

“His versatility is way better than I thought,” Hinch said one morning in Colorado. “We always talk about him as an athlete and him as a baseball player, his instincts and his feel for the game. It’s one thing to project that or predict it. It’s another thing to see it in play.”

Entering Tuesday’s game, Báez was not just playing well in center. He was playing the position at close to a Gold Glove level, worth four defensive runs saved in a small sample.

The Tigers have the best record in the American League — 28-15 after their latest victory — thanks largely to contributions like these, different players adapting to different roles, a roster that functions greater than the sum of its parts.

It’s hard to ignore the fact the Tigers have taken back-to-back games from the Boston Red Sox, the team that lured away white-whale free agent Alex Bregman this winter. The Red Sox are a good team. They have also already endured bouts of drama centered on Rafael Devers moving to DH, then refusing to play first base.

Across the way, the Tigers have a highly-paid player who has done more than accept taking on a new role.

Here in this new reality, Báez has thrived like no one saw coming.

“The second thing I’ve learned about him,” Hinch said, “is how much he cares about winning. … He doesn’t get enough credit for that. He doesn’t get enough love for that. I think because he’s not as outspoken or he’s not as open with fans and media that it gets overlooked. But I’m here to tell you that he’s all-in as a teammate, and that’s why we revere him.”

To understand what Javier Báez means to the Detroit Tigers, consider what happened last October.

It was the ALDS in Cleveland. Báez had been away from the team in Florida, rehabbing from surgery. The Tigers staged a remarkable run to the postseason without him. It was hard, at times, for Báez to watch and not feel part of it. Hurricanes kept him stranded in Florida during the wild-card round. But Báez made a point to be there for the next series.

“For me, it really sucked watching from outside,” Báez said. “I wanted to play the second half and in the playoffs.”

Báez can be quiet, to himself, a psychological puzzle managers have tried time and time again to solve. But for all his complications, Tigers teammates have always expressed admiration. No one has questioned his desire. Perhaps no greater evidence than the reaction when Báez walked in, and his teammates saw him for the first time in weeks.

“I think I was in the training room or something like that,” Matt Vierling said in October. “I saw him walk in, and, I mean, everybody in the training room kind of went nuts.”

So far this season, Báez has been basking in the glow of rejoining this team. He seems awakened by winning, energized by the challenge of playing outfield. He has talked of feeling healthy, able to sit straighter and swing better, somehow simultaneously hardened and softened by the perspective of time.

“One of the biggest things that I tell everybody is to enjoy it,” Báez said. “Sometimes you look back and you say, ‘I did not enjoy this,’ or ‘I should have done this better.’ I’m trying to let (my teammates) be themselves and play 100 percent free.”

One evening during spring training, Baez sat at dinner with Torres, his first-year teammate in Detroit.

“He shared: ‘I’m gonna hit better,’” Torres said.

So far, that prediction has proven correct.

“I think he feels better after surgery,” Torres said. “He’s healthy. He’s been doing good. I think confidence for him has been a big thing this year. How he handles every at-bat, it’s more focus on contact than to hit a homer. I think that’s a big key for him right now.”

A dive into the metrics does paint a less encouraging picture. Before Tuesday’s two-homer outburst, Báez’s 87 mph average exit velocity was a career low. He was benefiting from an otherworldly .398 batting average on balls in play. Although he is swinging less often than ever, the rate at which he is chasing bad pitches has crept back up over 40 percent, one of the highest rates in the league.

Little about Báez’s under-the-hood numbers — a 3.3 percent walk rate, an expected batting average of .247 — suggests he can keep performing at this pace.

And yet … Báez on Tuesday launched home runs at exit velocities of 106 and 99.4 mph. He helped the Tigers win not just with the walk-off moonshot where he posed and pushed the ball over the wall — ”Tried to do the Manny (Ramirez),” he said — but also with a small, heady play that has so long defined his game.

In the bottom of the third inning, Báez was creeping off third when Red Sox catcher Carlos Narváez received a pitch, then popped and fired toward the bag. Báez should have been picked off. But as he scampered back to the base, he broke inside the third-base line, nearly on the grass, disrupting the throwing lane.

“That is how you’re taught,” Hinch said.

Narváez’s throw hit Báez in the back. The ball trickled into left field. Báez turned and ran home uncontested. At third, Bregman looked at the umpire and protested.

“Honestly, I didn’t do that on purpose,” Báez said. I did move a little bit closer to the line, but I was just trying to get back to the bag.”

In a hard-fought game, the highlight homers do not matter without that run.

As for the best team in the American League? The Tigers likely would not be here without Báez, rejuvenated and redeemed.

Perhaps some of this is an El Mago illusion, bound to correct based on the numbers that rule this game. But here in the fourth year of his Tigers tenure, this captivating and fascinating player is performing his most mesmerizing act yet.

“It’s a great story for him personally,” Hinch said, “but it’s a great lesson for everyone. Just find a way to contribute to a win, and the game will reward you.”

(Photo: Nic Antaya / Getty Images)