Best-Yet ‘Baby Pictures’ of the Universe Unveiled

The final results from the Atacama Cosmology Telescope offer the sharpest, most sensitive view of the early cosmos that anyone has ever seen

The Atacama Cosmology Telescope, seen here on the Chilean peak of Cerro Toco, mapped the big bang’s afterglow from 2007 to 2022.

Mark Devlin, Deputy Director of the Atacama Cosmology Telescope and the Reese Flower Professor of Astronomy at the University of Pennsylvania

Sometimes, a picture can be worth much more than a thousand words. For instance, one measure associated with the pictures below—new high-definition snapshots of the cosmos in its infancy—is 1,900 “zetta-suns.”

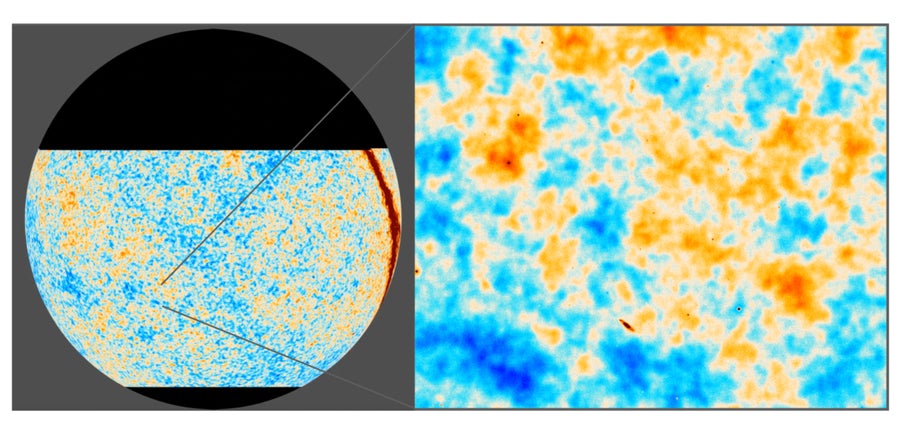

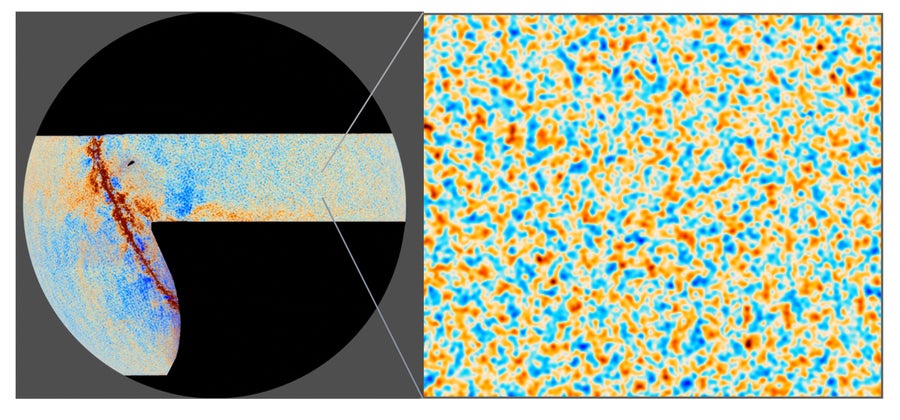

Two views of the cosmic microwave background (CMB), the afterglow of the big bang, as seen by the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT). The upper image shows ACT’s measurements of CMB temperature augmenting earlier measurements from the Planck satellite, while the lower image shows ACT’s measurements of CMB polarization. Blue and orange denote variations in temperature and polarization. Each image’s zoomed-in portion is 10 degrees across, or twenty times the Moon’ s width seen from Earth.

ACT Collaboration; ESA/Planck Collaboration

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Equivalent to almost two trillion trillion suns, that’s the amount of mass (or its counterpart as energy) that these images show to exist in the entire observable universe, which extends almost 50 billion light-years in all directions. The images, released today, are among the final results from the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT), a National Science Foundation–funded observatory that operated on a mountaintop in Chile from 2007 until 2022. The researchers will present their results, which have not yet been peer-reviewed, tomorrow at a meeting of the American Physical Society.

“What I love about these new images is how they bring the whole history of the universe to life,” says Jo Dunkley, a Princeton University cosmologist, who led the ACT analysis group. “The fact that you can just look out into the sky to see the whole sweep of cosmic time is beautiful. And with ACT, we’ve been able to see this better than ever before.”

What Did ACT See?

ACT observed the big bang’s afterglow, the cosmic microwave background (CMB), which was emitted when the universe was just 380,000 years old. Back then the cosmos was essentially a fireball, an expanding bubble of plasma as hot—and as opaque—as the surface of the sun. This opacity makes the CMB’s light the oldest that anyone can ever see. Building on past CMB surveys (such as that of the European Space Agency’s Planck satellite), ACT measured the intensity and polarization of the light emitted by this material with unprecedented sharpness and sensitivity. These values were then translated into estimates of the temperature, density and velocity of the swirling primordial stuff from which galaxies and larger cosmic structures would eventually coalesce. Those estimates in turn let ACT’s researchers effectively gauge the sum of all things and the way they came together.

How Much “Stuff” Is in the Universe?

Of the staggering 1,900 zetta-sun quantity the researchers came up with, only 100 zetta-suns come from normal matter: hydrogen makes up three quarters of the latter figure, and helium comprises the rest of it. Both of these elements emerged in the immediate aftermath of the big bang. All the rest of the elements—the carbon in your cells, the calcium in your bones, the oxygen you breathe and even the gold in your jewelry—showed up much later, after the ignition of the first stars, and are akin to a rounding error, just a meager sheen upon the greater cosmic ocean.

Of the remaining 1,800 zetta-suns’ worth of material out there, 500 zetta-suns represent dark matter, the invisible substance that serves as gravitational glue that holds galaxies together. But the bulk, some 1,300 zetta-suns, comes from the density of dark energy, the mysterious force that’s powering an acceleration in the rate of cosmic expansion. So most of the universe’s “stuff” is actually in the form of things for which we only have placeholder names—and a very limited understanding.

Why This Matters

Despite how little we seem to know, the most salient figure to assign to this all-encompassing “baby picture” of the cosmos arguably isn’t two trillion trillion suns (or a thousand words, for that matter). It is, in fact, six: the total number of core parameters that plug into the standard model of cosmology, called Lambda-CDM (with “Lambda” being a shorthand for dark energy and “CDM” referring to a sluggishly “cold” type of dark matter inferred from observations). Just six numbers, if properly arranged, seem to quite thoroughly explain the curious patterns imprinted on the CMB—and how they led to the cosmos we dwell in today.

Planck’s results had already suggested a similar conclusion. But with ACT’s five-times-higher resolution and three-times-greater sensitivity to polarization, researchers hoped to see signs of new physics beyond Lambda-CDM that its predecessor might have missed. “We came into this thinking the detailed patterns we’d see in ACT’s polarization data would reveal something about alternative cosmic models,” Dunkley says.

And it did—but not exactly as hoped.

What’s Next?

Rather than discovering telltale quirks that signpost a path to unraveling the nature of dark matter, dark energy and other cosmic mysteries, ACT’s results instead reinforced the soundness of the standard model of cosmology. The hoped-for breakthroughs may have to wait for fresh results from a new generation of CMB surveys, such as the Simons Observatory that’s now being built on the very same Chilean mountaintop that previously hosted ACT.

“The [Lambda-CDM] model just matches perfectly with all our data, which is pretty amazing, actually—that we’re able to look back to this earliest observable time, and this simple model is still working,” Dunkley says. “Something’s still missing from our understanding; we don’t know what dark matter and dark energy are, for example. But this result is important because it’s showing us that a lot of other things that could’ve made the universe more complicated aren’t happening. The early universe doesn’t seem to be where our problem lies.”