October 15, 2024

4 min read

Book Review: How the Author of Braiding Sweetgrass Imagines a New Economy

Robin Wall Kimmerer changed our ideas of sustainability. Can she do the same for economics?

Elva Etienne/Getty Images

NONFICTION

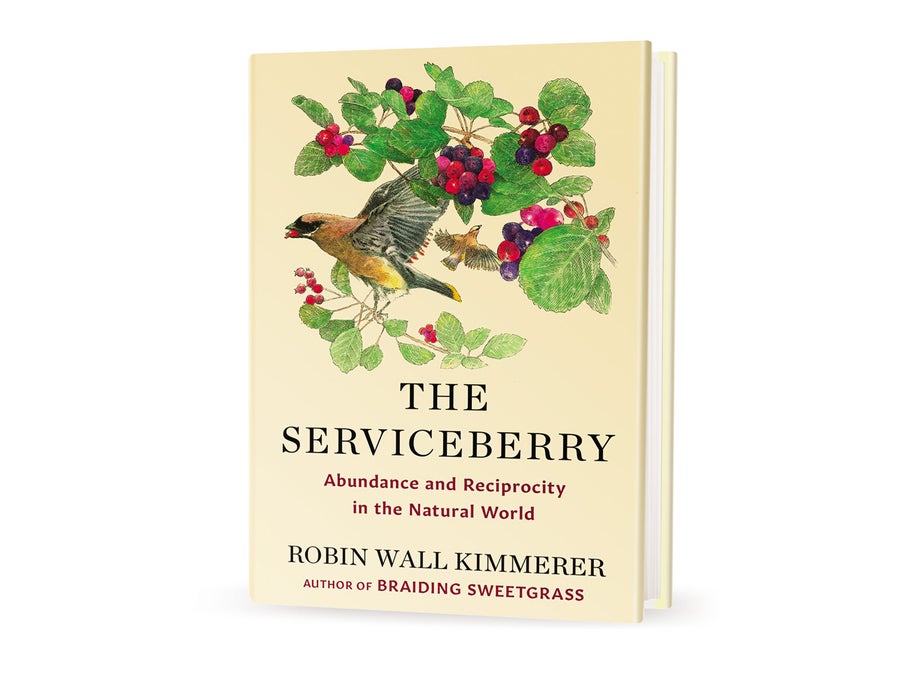

The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World

by Robin Wall Kimmerer.

Scribner, 2024 ($20)

Nature provides many gifts, but it is easy to take them for granted. It’s not just the strawberries you buy at the grocery store but also the plastic container that holds them, made of ancient life-forms transformed into fossils and then feedstock for plastics. How can we better recognize the value of the natural world and build communities—and economies—that acknowledge such abundance?

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

This is the central question of The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World. It’s the third book by Robin Wall Kimmerer, an ecologist, professor at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. For seven sleepy years, her last book, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants, published in 2013, quietly grew in popularity, until it leaped onto the New York Times bestseller list in 2020, where it has remained. It was as though Kimmerer’s concepts about animating nature and respecting nonhuman species as if they were people, told through the personal lens of an Indigenous scientist, struck a chord that was aching to be played. These ideas continue to reverberate: she is routinely invited to be a keynote speaker, her words are emblazoned on museum walls, and in 2022 she received the prestigious MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant.

The Serviceberry, which grew out of a 2022 essay in Emergence Magazine, is a much slimmer volume than Braiding Sweetgrass but is written with the same lyrical, personable voice that invites readers into worlds of possibility. In short chapters punctuated by line drawings from illustrator John Burgoyne, this sweet offering builds on her ideas about the gift economy and how Indigenous wisdom might inform it. She explores ancient guidelines known as the Honorable Harvest, her interpretation a bulleted manifesto for gratitude and how circular economies are a way to put these concepts into practice.

Kimmerer also continues her inquiry into language and what it reveals about worldviews. In the opening chapter, we learn Bozakmin is the Potawatomi word for “serviceberry,” a native shrub integral in Indigenous foodways that produces a blueberrylike fruit. Bozakmin is, literally, the “best of the berries,” and the Potawatomi root word for “berry” also means “gift.” Languages around the world offer examples that demonstrate the deeper connections we once had to the earth that very literally sustains us. The Greek word oikos, Kimmerer writes, is the root for both “ecology” and “economy.”

Oh, but how we’ve forgotten the link! As Kimmerer fills a pail with an abundance of serviceberries in the opening scene, a flock of cedar waxwings joining her in the harvest, she sees the fruit as “a pure gift from the land. I have not earned, paid for, nor labored for them.” She urges readers to take note of the small bequests that abound, which remind us we live in a world of reciprocity where giving can be liberated from an artificial market that manufactures scarcity and individual desire: Little Free Libraries on front lawns and free boxes of clothes and the invitation from a neighbor to come pick berries for free.

Kimmerer admits this way of generous living—intimate with both the land and one’s neighbors—works best in small, close-knit communities. Yet more than half the world’s population now lives in urban environments, and the flow from country to city continues. Given this context, how do we, as she writes, “reclaim ourselves as neighbors”? If serviceberries were a marketable commodity, I can’t help but wonder, would her neighbors have opened their farm to her for a free day of harvesting? I wanted her to wrestle more with the capitalist juggernaut in which nearly all of us are enmeshed, one dominated by the schemes of people untroubled by destroying what others love in the name of profit.

“Recognizing ‘enoughness’ is a radical act,” she writes, “in an economy that is always urging us to consume more.” Recognition is one step. Transforming economies is something else altogether. Kimmerer, who donated her book advance to land conservation and social justice work, writes that she knows little of economics or finance. Although she seeks understanding through books and conversations, she seems to struggle the way many of us do with how such ideas would scale.

The answer, Kimmerer writes in the last and strongest chapter, is to look to ecological succession in the natural world, where disturbances cause seemingly intransient systems to transform. Capitalism may not crumble, but we could pursue conditions for economic succession to a space where reciprocity is recognized. Not just by imagining another way to be in the world but by creating it. Many plants and animals go dormant, waiting for the right moment to resurface and come fully alive again. Can ideas and ways of being, like rhizomes reaching through soil, do the same?