Have you ever stood by the sea and been overwhelmed by its vastness, by how quickly it could roll in and swallow you? Evidence suggests that we are suspended in a cosmic sea of dark matter, a mysterious substance that shapes galaxies and large structures in the universe but is transparent to photons, the carriers of the electromagnetic force. Our galactic home, the Milky Way, is submerged in dark matter, but this hidden body but does not devour us, because its forces cannot touch the regular matter we’re made of.

Everything we know about dark matter comes from measuring its gravitational pull, but gravity is the weakest of nature’s forces—so feeble that the electromagnetic forces that bind atoms to make a chair we can sit in are enough to counteract the gravitational force of the entire Earth. Just as we need the electromagnetic force to tell us about protons, neutrons, electrons and the richness of all the particles we know of—collectively called the Standard Model of particle physics—we need more than gravity to unlock the secrets of the dark side. As a result, the past three decades of the search for dark matter have been characterized by null results. For most of that time, researchers have been looking for a single particle to explain dark matter.

Yet dark matter might not be one particular particle—it may be a whole hidden sector of dark particles and forces. In this dark sector, particles would interact through their own independent forces and dynamics, creating a hidden world of cosmology running parallel to our own. There could be dark atoms—made of dark protons, dark neutrons and dark electrons—held together by a dark version of electromagnetism. The carriers of this force, the dark photons, might (unlike our photons) have mass, allowing huge dark atomic nuclei—so-called nuggets—to form. And the totally different dynamics of dark matter in this dark sector would have different effects on the evolution of normal matter throughout time. The interactions of nuggets in galaxies could help form supermassive black holes in the centers of galaxies, causing them to grow larger than they otherwise would.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Dark matter might not be one particular particle—it may be a whole hidden sector of dark particles and forces.

As other, simpler theories of dark matter have failed to find experimental confirmation, the dark sector concept has gained traction. My colleagues and I have also developed novel plans for experiments that can search for this type of dark matter. These experiments use techniques from condensed matter physics to attempt to uncover a sector of the cosmos we’ve never searched for before.

When I entered the dark matter hunt in 2005, physicists were focused on searching for dark matter whispers from the weak force. Despite its name, the weak force is much stronger than gravity, and scientists suspected that dark matter might communicate with our world through this force. They built many extremely sensitive experiments, buried underground where everything is quiet, to attempt to hear such murmurs.

It was an exciting time because astrophysicists were also seeing unexplained data coming from the center of the Milky Way that might have been a sign of dark matter producing a haze of photons from some kind of interaction with the weak force. I found these ideas intriguing, but I wasn’t convinced that the Milky Way signal came from dark matter. It seemed premature to focus the search for dark matter on theories related to the weak force. In addition, many processes from ordinary physics produce the microwave photons that were emanating from the center of our galaxy.

At the first dark matter conference I attended after graduate school, I took a bet with a primary proponent of the “dark matter haze” idea, Dan Hooper of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Hooper thought we could confirm that these observations were caused by dark matter within the next five years. I took the skeptical position. The stakes of the bet: whoever lost would have to say that the other was right in each of their scientific talks for one year. It was a consolation that if I lost, I could still bask in the joy of dark matter having been discovered. This bet would accompany me for the next 13 years of my scientific career.

Sometimes our assumptions end up binding us, preventing us from finding the solutions we seek. The first ideas for the nature of dark matter focused on solving the theoretical problems of the Standard Model, which describes not just the known particles but the quantum forces (electromagnetism, the weak force and the strong force). Two puzzles of the model are why the weak force is so much stronger than gravity (what physicists call the hierarchy problem) and why the strong force—the force that binds atomic nuclei—doesn’t notice the difference between mirrored particles and antiparticles (called the strong charge conjugation–parity, or strong CP, problem). Particle physicists hypothesized that adding new particles to the Standard Model could help us understand why the known particles behave like they do. These new particles might also exist in the right quantities to explain dark matter.

Two categories of particles emerged as popular candidates. One group, called WIMPs (for weakly interacting massive particles, lest you doubt the field has humor), features in solutions to the hierarchy problem. Another set of proposed particles, axions (after the laundry detergent, as a metaphor for cleaning up the problem), offered a solution to the strong CP problem.

I thought, however, that we should question the premise that dark matter also solved the Standard Model problems. My imagined particles didn’t interact via any Standard Model forces—they would have their own independent forces and dynamics—so they couldn’t solve that model’s mysteries. They were also much lower in mass than WIMPs and occupied a hidden valley of the energy and mass scale for particles. This idea, which I proposed around 2006, went counter to the trend in high-energy physics, which focused on building huge experiments, such as CERN’s Large Hadron Collider near Geneva, to produce the increasingly massive particles that theorists envisioned. In contrast, hidden valley particles would occupy much lower-energy territory and may not have been observed in experiments simply because their interactions with ordinary particles are much weaker than the weak force.

Without the idea that dark matter should solve either the hierarchy problem or the strong CP problem, an entire range of new models became theoretically viable and consistent with observations of our universe. I focused on the idea that the hidden valley provided a natural host for the dark matter sector. The different dynamics of dark matter in the dark sector compared with WIMPs would have different effects on the evolution of normal matter throughout time.

As my colleagues and I studied the possible implications of a dark sector over the next decades, the range of observable consequences in our universe blossomed. The field looks completely different now. Dark sector theories have been aided along the way by fortuitous experimental anomalies.

The lucky anomalies arrived in 2008 from experiments that had been looking for WIMP dark matter. By this time experimentalists had already spent two decades building Earth-based experiments to look for dark matter from the supposed sea that must be passing through Earth at all times. In 2008 three of these saw a mysterious, unexplained rise in “events” at low energies. An event, in this case, means that a single dark matter particle may have slammed into a regular atomic nucleus in the detector and given it a kick of energy. The experiments registered events that could have been caused by dark matter particles weighing a few times the mass of the neutron.

The excesses in these experiments electrified me because they were consistent with a theory of hidden valley dark matter I had proposed the previous year. I called this theory asymmetric dark matter. The theory was based on the idea that the amount of dark matter in the universe is determined by how that matter interacts with neutrons and electrons. We can take this number, set by theory, and combine it with the total mass of all the dark matter in space (which we know from astronomical observations) to calculate the mass of the most common dark sector particles. It turns out that the theorized particles should weigh about as much as neutrons—just what the experiments were observing.

The arrival of these anomalies made the field of hidden sector dark matter very popular. The online repository for new physics papers exploded with studies suggesting possible explanations for the excesses with different types of hidden sectors. It suddenly seemed I might lose my bet that dark matter would keep itself hidden. But the observations and the theories weren’t quite lining up, and the models became more baroque and contorted to fit the experimental data. By 2011 my belief that the anomalies could be evidence of dark matter faded.

Not everyone agreed. Hooper, ever the optimist, still thought that the anomalies could be dark matter, so he upped the bet and threw in two top-shelf bottles of wine. Eventually, though, further checks of the anomalies convinced most physicists that most of the observations must have a mundane explanation, such as a background signal or detector effects contaminating the data. My top-shelf bottles of wine from Hooper arrived during the pandemic in 2020.

But that wasn’t the end of the story. The long-term impact of these anomalies opened researchers’ minds to new theories of dark matter beyond WIMPs and axions. This change was aided by the fact that decades’ worth of experiments designed to find WIMPs and axions had so far turned up nothing. Even the Large Hadron Collider, which many scientists expected to find WIMPs and other new particles, found nothing new except for the last unconfirmed piece of the Standard Model, the Higgs boson. More and more physicists recognized that we needed to widen our search.

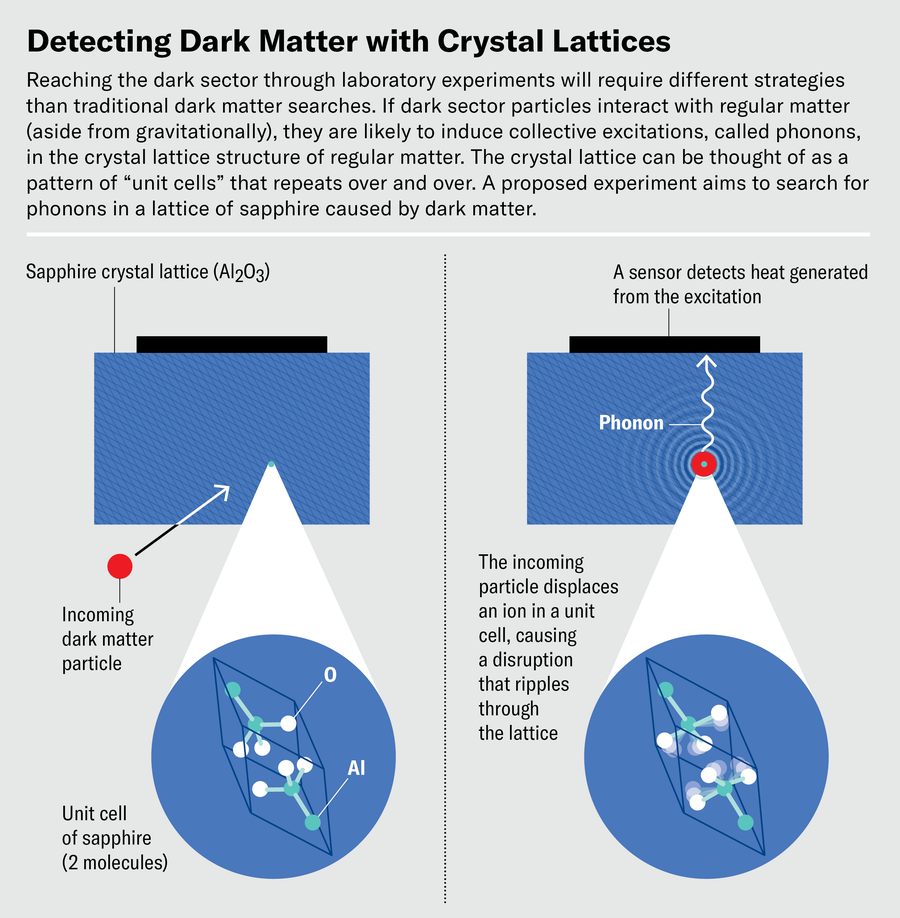

In 2014 I moved from the University of Michigan to Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, where I turned my attention from dark matter theories to devising new methods of dark matter detection. Working in this area radically broadened my horizons in physics. I learned that studying the fundamental forces of nature is not sufficient to understand how dark matter might interact with regular matter. For such rare and weak communications between particles, the interactions between the fundamental constituents of matter (the nucleons and electrons in atoms) become paramount. In other words, to understand how a dark matter particle might affect a typical atom, we must consider the small interactions among the atoms arranged in a crystal lattice inside a material. Imagine the coils in an old-fashioned mattress: if one part of a coil gets pushed down, it propagates waves through the entire mattress.

Because many materials work like this, it stood to reason that if dark matter were to disturb one atom in a lattice of “normal” matter, it would set up a propagating disturbance. These collective disturbances, which involve many atoms, are quantum in nature and are called phonons or magnons. Understanding phonons is the domain of condensed matter and solid state physics, which focus on the collective effects of many atoms within a material. Because materials can be made up of lots of different kinds of atoms and molecules, with different bonds between them, the collective disturbances take on many forms, becoming a zoo of possible interactions.

What we have achieved in the past 20 years is a dramatic opening of the theoretical possibilities for dark matter and the ways to find it.

One of my challenges was to understand how dark matter might interact with these collective phenomena. To do that, I needed a useful model that described all the complicated effects with just a few parameters. I found that I could predict how likely different kinds of dark matter were to interact with a material if the force governing the interaction was the same as the force responsible for dark matter’s abundance in our universe.

I ran into some practical challenges. Not all physicists speak the same physics language. In addition, each field tends to focus on just a few questions when studying a physical system. I was interested in very different questions than those that interest most practicing condensed matter physicists. And as a dark matter physicist collaborating with condensed matter physicists on collective excitations for the first time, I had barriers to surmount. Once I discovered how to rephrase my understanding of the dark matter interaction problem in the jargon used by condensed matter and atomic physicists, my students, postdocs and I were able to progress much more quickly.

In time, a new world of collective phenomena opened before us. We discovered that condensed matter and atomic, molecular and optical physicists had fun applying their portfolio of materials and detection mechanisms to the hunt for dark matter. After a few years of playing with an abundant array of ideas, we realized we needed to focus on just a few for experimental development. We ended up picking two materials that seemed like promising targets, both for their fundamental dark matter interactions and for how feasible their use in experiments was. Now we are actively designing experiments using these materials that we hope to run in the coming years.

The first category is polar materials, such as quartz and sapphire, which produce strong phonons with a collective energy that is a good match for dark matter and which seem like they would communicate well with a dark photon. The second material is superfluid helium, which is free from many of the defects that plague solid materials with crystal lattices. This liquid features light nuclei that may have a relatively good chance of interacting with dark matter.

For the next steps, our experimental partners are leading the way. My former Lawrence Berkeley Lab colleagues have developed two of the most promising ideas. Matt C. Pyle has proposed an experiment called SPICE (Sub-eV Polar Interactions Cryogenic Experiment), which would use a polar material such as sapphire for a detector. Another experimentalist, Daniel N. McKinsey, has envisioned the HeRaLD (Helium and Roton Liquid Detector) project, which would use superfluid helium.

Our theoretical work suggests that small samples of the target materials—one kilogram or less—could be enough to begin testing our theories. Although these samples would not require much material, they would have to be free of defects and be placed in very quiet and contaminant-free environments. Fortunately, through earlier generations of dark matter experiments searching for WIMPs, Pyle and McKinsey already have experience in reducing sources of noise and radioactivity by working deep underground.

Although all the theoretical ideas are in place for these experiments, it will take a long time to put them into action. Both projects have received a round of funding from the Department of Energy’s Office of Science to further develop the concepts. Over the past four to five years, however, we’ve discovered new background processes that might imitate the signals we’re hunting for, which we’ll have to find ways to block. Because of these large backgrounds, the detectors are not nearly sensitive enough yet to discover dark matter. It may take a decade or more, as it did for the earlier generations of WIMP experiments, to learn how to make these detectors so quiet that they can listen for dark matter whispers.

Still, what we have achieved in the past 20 years is a dramatic opening of the theoretical possibilities for dark matter and the ways to find it. The fundamental nature of the dark matter that pervades our universe is still unresolved. As I work on this problem, I like to think about the building of cathedrals in centuries past, which were constructed over generations, each stone carefully placed on the last. Eventually, by building our understanding of dark matter bit by bit, we hope to reach a true comprehension of all of nature’s constituents.