My favorite Rickey Henderson story is one told by former major leaguer and MLB Network personality Harold Reynolds. It never gets old.

The year is 1987. Henderson, dealing with hamstring issues, appears in only 95 games for the New York Yankees. Reynolds, playing for the Seattle Mariners, leads the American League with 60 stolen bases — the only season from 1980 to ’91 in which Henderson did not top the AL in steals.

“I get home. The season ends. The phone rings. ‘Henderson here’ — he always talks in the third person,” Reynolds said on The Dan Patrick Show in 2019. “I said, ‘What’s up, Rick?’ He goes, ‘Man, you ought to be ashamed.’ I go, ‘What are you talking about?’ He says, ‘60 stolen bases. You ought to be ashamed. Rickey has 60 at the break.’ Click. Hung up.’”

The story is vintage Rickey, boastful, colorful — and yes, truthful, too. One can argue about Henderson’s place among baseball’s all-time greats: Top five? Top 10? Top 20? No one, however, can argue with the fact that he was the greatest stolen-base threat in the game’s history.

The loss of Henderson, who died Friday, is another blow to the storied legacy of baseball in Oakland, and in some ways the biggest yet. Henderson played for nine clubs in his 25-year career, but left his biggest mark with his hometown team, beginning his career with the A’s and playing for them in parts or all of 14 seasons.

The A’s played their final game in Oakland just three months ago, but no one can erase the city’s rich baseball history. The late Frank Robinson was from Oakland. So was fellow Hall of Famer Joe Morgan, as well as Curt Flood, Jimmy Rollins, Dave Stewart and Dontrelle Willis. And then there was Rickey.

From the moment he debuted in 1979, he was an electrifying performer, as charismatic as they come. Yet for all of his wondrous accomplishments — his .401 career on-base percentage, his 10 All-Star appearances, his two World Series titles — he is perhaps best known as the “Man of Steal.”

Henderson finished with a record 1,406 stolen bases. In 1980, his first full season, he stole 100 to break Ty Cobb’s 65-year American League stolen-base record. In 1982, he stole 130 to break Lou Brock’s single-season mark. In 1998, at age 39 — 39! — he stole 66 to lead the AL.

If he had played under rules Major League Baseball implemented to juice stolen-base totals in 2023 — a maximum of three pickoff attempts or stepoffs per plate appearance, larger bases to reduce the length between first and second and second and third by 4 1/2 inches — heaven knows what Henderson’s career total might have been.

Actually, Rickey had an idea.

“Oh, I’d say 1,600 or 1,700,” he told The Athletic’s Britt Ghiroli in March 2023.

Henderson might have been selling himself short. The league’s stolen-base total spiked by 41 percent from 2022 to ‘23, and jumped another 3 percent from 2023 to ‘24. Do the math. An increase in Henderson’s career stolen-base total by 41 percent would have left him with nearly 2,000.

As Henderson might have noted himself, Rickey didn’t need bigger bases. Rickey didn’t need a disengagement rule. And Rickey certainly didn’t need any help.

As the game mourns one of its shining lights, it’s worth updating Henderson’s original message to Reynolds, all in good fun.

Elly De La Cruz, who led the NL last season with 67 stolen bases? José Caballero, who led the AL with 44?

You ought to be ashamed. Under the new rules, Rickey would have obliterated those totals faster than you can say, “Man of Steal.”

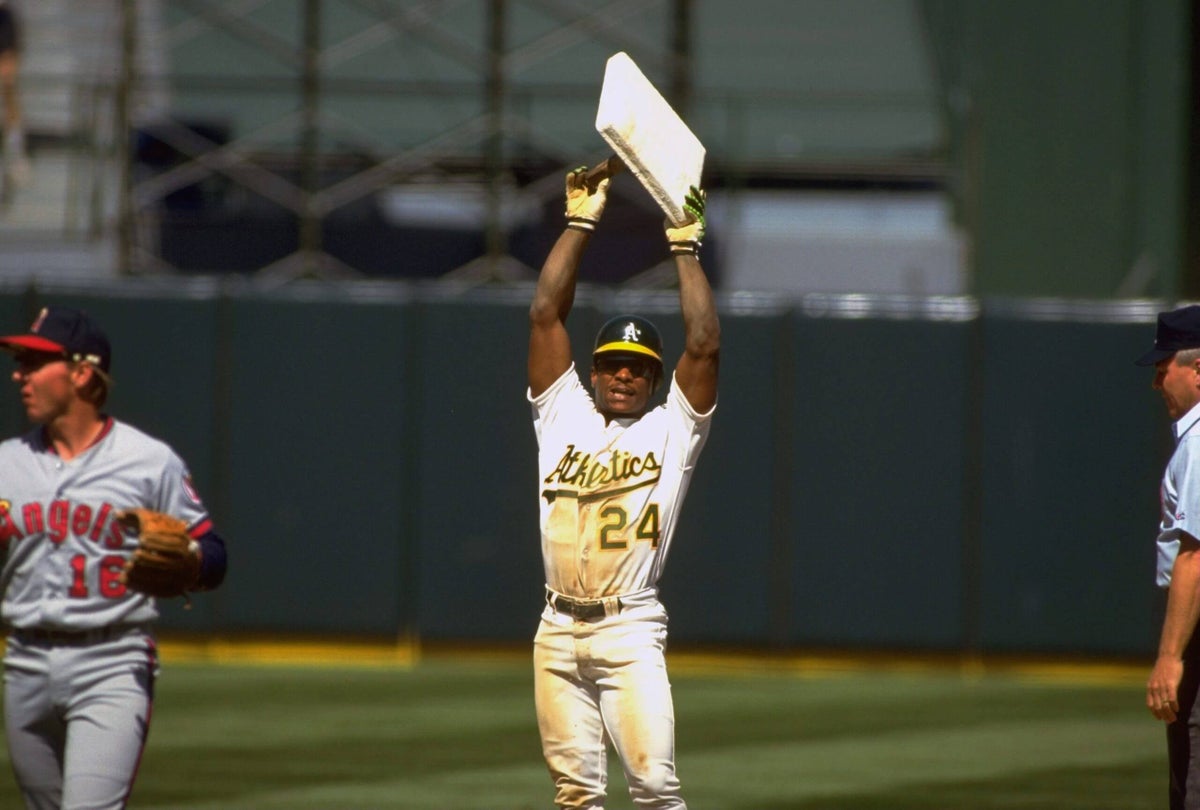

(Top photo of Henderson after tying Lou Brock’s career stolen-base record in 1991: Richard Mackson / Sports Illustrated via Getty Images)