September 17, 2024

3 min read

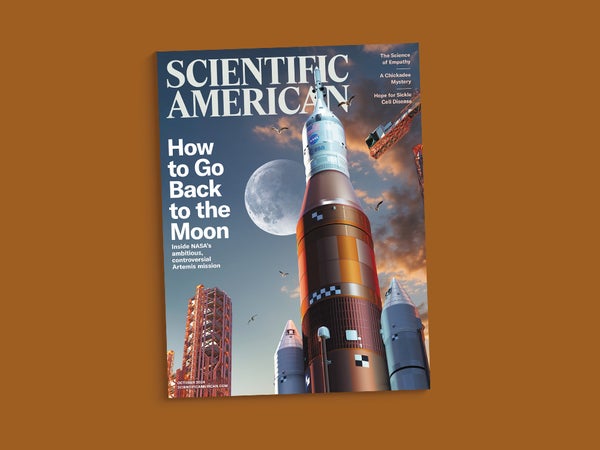

Going Back to the Moon, Researching Chickadee Hybrids and Understanding Addiction

This month’s issue covers the reasons it’s so hard to go back to the moon, the science of empathy and new advances in treating sickle cell disease

Scientific American, October 2024

There’s something special about chickadees. They’re curious (they’ll come investigate if you make a pish-pish-pish sound), they’re smart (they stash seeds to eat over the winter), and they’re so stinking cute. I appreciate a bird that tells you what it is: Whip-poor-will! Bob-white! Chick-a-dee-dee-dee! And there’s a lot of hidden drama in chickadees’ world, as author Rebecca Heisman relates.

Multiple species of chickadees live in North America, and it can be tough to tell them apart. To complicate matters, they don’t always make much of a distinction: Carolina Chickadees and Black-capped Chickadees regularly mate in the East, as do Black-caps and Mountain Chickadees in the West. (I hope this is some comfort to anybody who has struggled to identify a chickadee’s species using a field guide.) Research on hybrid chickadees is revealing how species maintain their boundaries, how birds are specialized for their habitats, and how reckless pairings can occur when a new species moves into another’s territory.

Our cover story this month started with what seemed like a simple question: Why is it so hard to get back to the moon? I mean, obviously rocket science is rocket science—complex, dangerous, pitiless. But we figured it out more than 50 years ago, which is eons ago in computer years. Scientific American contributing editor Sarah Scoles explores the surprising technological and social reasons that the Artemis II flight, scheduled to lift off next year (but don’t mark your calendar), seems so much more challenging than the Apollo missions.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Empathy is a complex skill that can improve with training—and researchers have experimented with many different types of training. Regardless of the age of participants or the different backgrounds and experiences that separate them, some patterns come through: listening and being listened to improve empathy, as do perspective taking and practice. But what really matters is motivation because empathy can be cognitively and emotionally exhausting. Supporting empathy as a social norm can make it easier and more rewarding to understand other people. Science writer Elizabeth Svoboda covers the latest science on empathy here.

The opioid overdose epidemic has been one of the most horrific and deadly disasters of the century. The death rate seems to be coming down after what we hope was the peak, during the COVID pandemic. We desperately need better and more treatments for people with addiction, and author Maia Szalavitz describes the evidence supporting a new approach. People who have experienced childhood trauma are at greater risk of addiction, and treating the trauma can be the most robust way to prevent or manage addiction.

Learning about sickle cell disease is a great way to understand the history of modern medicine, with all its triumphs and failures. It was the first disease to be understood at the molecular and genetic levels. It shaped our understanding of how evolution can influence disease. And it starkly shows how systemic bias and exclusion can impair research and health care and harm people. Finally, new treatments can now cure sickle cell disease.

Our Innovations In special report on sickle cell disease, shares perspectives from patients, advocates, clinicians and scientists. It describes the newly available therapies and others in development, featuring a great series of graphics that show ingenious techniques for restoring healthy blood cells. Research on sickle cell is generating valuable insights on chronic and acute pain. And the package demonstrates that making science more inclusive and just can lead to better lives for all.