October 15, 2024

3 min read

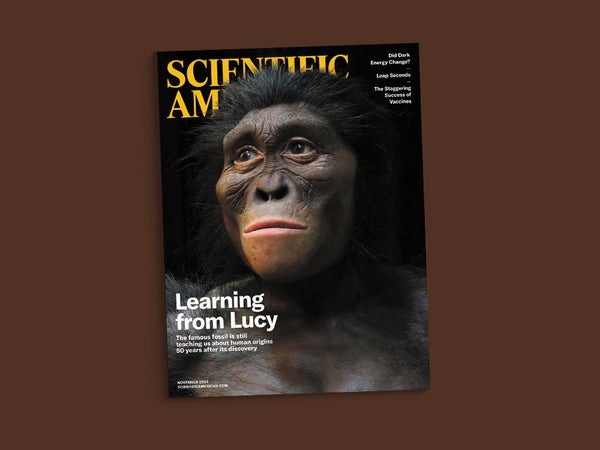

Lucy Turns 50, and Dark Energy Gets More Mysterious

What works to improve health equity? And it might be time to end the leap second

Scientific American, November 2024

Something strange is happening with dark energy. What little we know about it is strange enough: “Dark energy” is the name for an unknown force that is causing the universe to expand faster all the time. Nobody has been able to detect dark energy directly; we can only measure its effects. And one of those measurements is a little … off. The Hubble constant describes how quickly the universe is expanding. Physicists estimate its value in the nearby universe by measuring distances to supernovae.

The problem is that these estimates for the Hubble constant don’t match what the standard model of cosmology predicts based on patterns in the cosmic microwave background, the glow left over from the early universe. The discrepancy has gotten more pronounced (and less likely to be a measurement error) in the past few years with more precise observations from the James Webb Space Telescope, building on those from the Hubble Space Telescope.

So has dark energy changed over the course of the universe? Did an additional “early dark energy” force give the universe some extra oomph immediately after the big bang? Theoretical physicist Marc Kamionkowski and astrophysicist Adam G. Riess have been working on this “Hubble tension” problem from the beginning. They explain the problem and possible solutions as clearly and entertainingly as I’ve ever seen (as always, great graphics help).

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The Australopithecus afarensis fossil fondly known as Lucy is one of the most important discoveries in the study of human origins. She was found 50 years ago and quickly changed our understanding of how we became human. Her discoverer, Donald C. Johanson, and paleoanthropologist Yohannes Haile-Selassie, who has discovered many other crucial hominin ancestors, share what we’ve learned about the evolution of human brains, gait, habitats and diets by studying these precious fossils.

Earth’s daily rotation has slowed down over time; when dinosaurs roamed the planet, a day lasted just 23.5 hours. This consistent slowing is mostly because of friction. The gravitational pull of the moon causes ocean tides, and the friction of the oceans sliding across the seafloor slows the entire system. Inside the planet, currents in the liquid outer core are now slightly increasing our rotational speed. And global warming is changing the dynamics of Earth’s rotation as well, as water from melting ice moves from the poles toward the equator. It’s a mess. We have added “leap seconds” over the years to synchronize atomic clocks with Earth’s changing rotation. Senior editor Mark Fischetti, working with infographic designer Matthew Twombly, asks if it’s time to just let clock time and planetary time drift apart.

Vaccines delivered through a puff up the nose or into the mouth could be even more effective than shots at protecting people from respiratory diseases (plus, no needles). Science journalist Stephani Sutherland covers the progress that is being made on nasal vaccines and the reasons scientists are so hopeful about them.

We’re publishing our third annual special package on health equity in this issue, with a focus on solutions. Here are some highlights: Vaccines are among the most lifesaving interventions in the history of humanity. People working in rural areas have come up with innovations that have improved medical care for all. Disaggregating data improperly lumped together can save lives. Medical devices and algorithms are being corrected for historical biases. And we talked to several experts in global health about what gives them hope for the future. We hope the collection is inspiring—it has been for us at Scientific American.