This year is the centennial of the discovery of human brain waves. Few people know the story of that startling finding, because the true story was suppressed and lost to history. Almost two decades ago I visited the pioneering scientists’ labs in Germany and Italy seeking answers. What I learned overturned accepted history and exposed a chilling tale involving Nazis, brainwaves, war between Russia and Ukraine, and suicide. This history resonates with current events—Russia and Ukraine recently passed a grim 1,000-day milestone of a conflict waged on a pretext of battling Nazis—revealing how history, science and society are intricately entwined.

Human brainwaves, oscillating waves of electricity that constantly sweep through brain tissue, change with our thoughts and perceptions. Their value in medicine is incalculable. They reveal all manner of neurological and psychological disorders to doctors and guide neurosurgeons’ hands when extracting diseased brain tissue that triggers seizures. Only newly appreciated, their role in the healthy brain is transforming our fundamental understanding of how the brain processes information. Like waves of all types, the electrical waves sweeping through the brain generate synchrony (think of water waves bobbing boats); in the case of brainwaves, what’s synchronized is activity among populations of neurons.

Who discovered brainwaves? What did they think they’d found? Why was there no Nobel Prize?

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

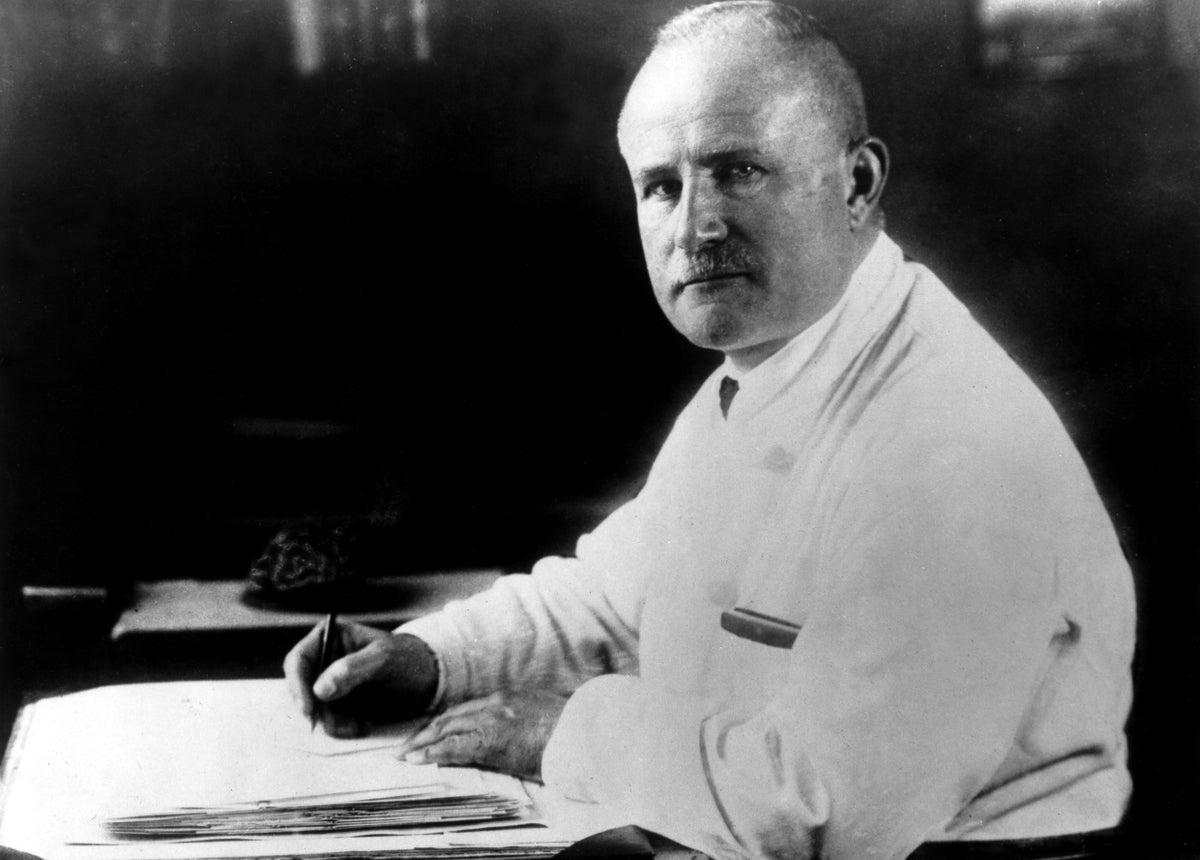

In the most common accounts, a reclusive physician, Hans Berger, recorded the first human brainwaves from his patients in a mental hospital in the German city of Jena in 1924 (later part of East Germany). He told no one what he was doing, and he kept his momentous findings secret for five years. As the Nazis rose to power in the 1930s, mental hospitals became the epicenter of forced sterilization and “euthanasia” to promote “racial hygiene.” Some of the methods developed in these facilities served as a prelude to the industrialized killing in concentration camps. As head of the mental hospital in Jena, Berger would have been in the thick of it. Biographies at the time of my visit stated that Berger committed suicide in 1941 from Nazi persecution

‘‘Berger was no adherent of Hitler and so he had to relinquish the service of his University; not having expected this, he was gravely hurt…. [This] bestowed upon him a depression which finally killed him,’’ wrote psychiatrist Rudolf Lemke, in a 1956 memorial. Lemke had worked under Berger.

To me this seemed odd. Wouldn’t the Nazis have dismissed Berger just as they purged 20 percent of German academics in 1933, and ruthlessly expelled or “liquidated” disloyal politicians, administrators and others?

In Jena I learned that Lemke was in fact a member of the NSDP (Nazi party). He worked at the Erbgesundheitsgericht (Hereditary Health Court) to carry out forced sterilization of the mentally and physically unfit, broadly defined as the physically disabled, psychiatric patients, alcoholics, among others. Like many others in power, Lemke stayed on in Jena after the war, and his antisemitic and antihomosexual views were covered up by authorities. He became director of the Psychiatric Clinic in Jena from 1945 until 1948.

After World War II Jena came under control of the Soviet Union, and documents revealing the widespread cover-up were lost or destroyed. When I visited Berger’s hospital I met with neuroscientist Christoph Redies and medical historian Susanne Zimmermann, who had recently obtained Soviet records after the fall of the Berlin wall. They revealed that Berger was, in fact, a Nazi sympathizer. He committed suicide in the hospital, not in protest but because he suffered from depression, she says. In taking his own life, Berger’s death mirrored the suicides of many others at the time who were involved in Nazi atrocities.

Leafing through his dusty laboratory notebooks containing the earliest recordings of human brainwaves, Zimmermann pointed out marginal antisemitic comments he had written alongside them. She then pulled out a stack of records of proceedings in the forced sterilization court where Berger served in an era when “eugenics” sought to cull the “unfit” from parenthood. Hearing them read aloud brought to life the horrors that had taken place there, as people pleaded with the court not to sterilize them or their loved ones. Berger denied every appeal, condemning them all to forced sterilization.

The hospital in Jena, Germany, where Berger discovered brainwaves.

Berger’s EEG research was not well received. A believer in mental telepathy, Berger thought brainwaves could be the basis for mental telepathy, but he ultimately rejected that idea. Instead, he believed that brainwaves were a type of psychic energy. Like other forms of energy, waves of psychic energy could not be created or destroyed, but they could interact with physical phenomena. Based on this, he surmised that the work of mental cognition would cause temperature changes in the brain. He explored this idea by stabbing rectal thermometers into his mental patients’ brains while they did cognitive tasks during surgery.

Berger’s research remained little known outside Germany until 1934 when Nobel Prize–winning neuroscientist Edgar Adrian published his experiments in the prestigious journal Brain. Adrian confirmed that the so-called “Berger waves” do exist, but he implicitly mocked them by showing that they changed in a water beetle when it opened and closed its eyes, in the same way they did in the Nobel Prize–winner’s brain when he did the same. Adrian never did further research on brainwaves.

Berger is credited with the discovery of brainwaves in humans, but studies in animals predated his work. Nor did Berger invent the methods he used to monitor brain activity. He applied techniques used previously in animal experiments by Adolf Beck in Lwów, Poland, in 1895, and Angelo Mosel in Turin, Italy.

In contrast to Berger, Adolf Beck’s animal studies were intended to understand how the brain functions when neurons communicate by electrical impulses. At the peak of his research a Russian invasion halted his scientific work. In 1914 Lwów was taken by invading Russians and renamed Lviv. Beck was captured and imprisoned in Kiev, then part of Russia (now Kyiv, Ukraine).

While in prison he wrote to the famous Russian scientist Ivan Pavlov appealing for his help, and Pavlov eventually won Beck’s release.

Beck returned to his research in Lviv, and the next logical step was to search for brainwaves in humans, but in World War II Germans invaded. They established a concentration camp in Lviv where the Jewish population was exterminated. As an intellectual and a Jew, Beck was a target. When they came to take Beck to the concentration camp in 1942, he swallowed cyanide, ending his own life rather than having it taken by the Nazis.

Remarkably, both pioneering brainwave scientists committed suicide from Nazism—one as Nazi perpetrator, the other as Nazi victim.

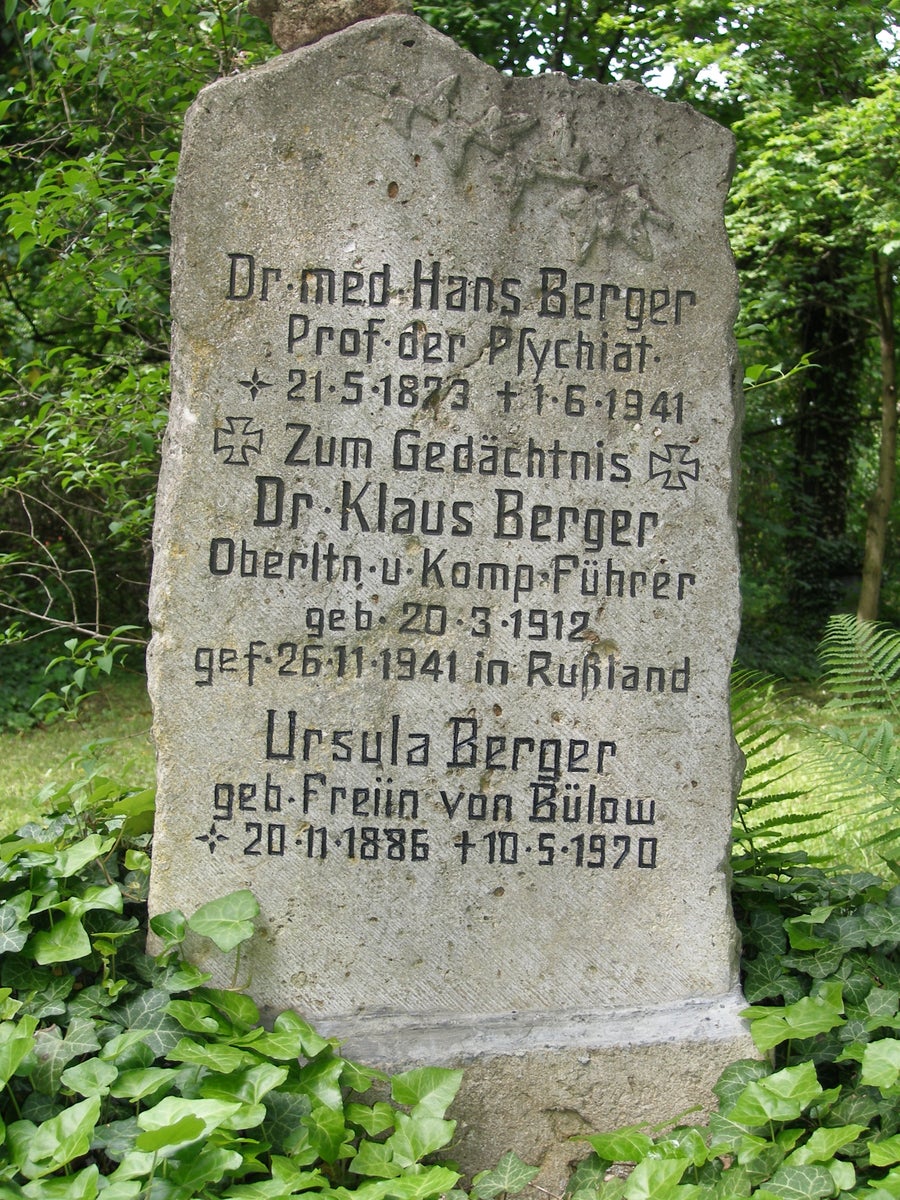

Berger’s grave in Jena.

Unknown to both Berger and Beck, they were not the first to record brainwaves. That discovery was made by a London physician 50 years earlier than Berger! That stunning finding was lost to science because the ideas were so far ahead of their time, dating back to when the brain was an enigma and the world was lit by gas lamps and powered by steam. Imagine how much further ahead brain science and medicine would be now if this scientific discovery made in 1875 had not been lost to history for half a century.

The first person to discover brainwaves was the London physician Richard Caton. Caton announced his discovery of brainwaves recorded in rabbits and monkey at the annual meeting of the British Medical Association in Edinburgh in 1875. He achieved this using a primitive device, a string galvanometer, in which a small mirror is suspended on a thread between magnets. When an electric current (picked up from the brain in this case) passes through the device, the string twists slightly like a compass needle near a magnet. The oscillating electrical currents detected in the brains were not measured in volts, but rather in millimeters of deflection of the light beam bounced off the mirror. The published abstract of his presentation “The Electric Currents of the Brain” shows that with this primitive instrument the physician correctly deduced the most important aspects of brainwaves. “In every brain hitherto examined, the galvanometer has indicated the existence of electric currents…. The electric currents of the grey matter appear to have a relation to its function….”

Ironically, I traveled the world to research the discovery of brainwaves, only to find that the first person to do so, Richard Caton, presented his findings in the U.S. in 1887 at Georgetown University while on a visit to his family in Catonsville, Md. The town, which was settled by his relatives 1787, is 30 miles from my home, next to the Baltimore-Washington Airport, from which I often embarked on my global search. But that fact, like his unappreciated brainwave research, was lost to history. “Read my paper on the electrical currents of the brain,” he wrote in his diary. “It was well received but not understood by most of the audience.”

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.