Members of the U.S. congress whose ancestors enslaved people have had a higher median net worth than those whose ancestors did not, according to a new analysis published on Wednesday in PLOS ONE.

The analysis used genealogical data published last year by an investigative team at Reuters, which found that in 2021, at least 100 members of Congress were descended from enslavers. This included 8 percent of Democrats and 28 percent of Republicans.

This reporting caught the eye of Neil K. R. Sehgal, a Ph.D. student and computational social science researcher at the University of Pennsylvania. He wondered what this unique genealogical data might reveal when combined with other publicly available information about members of Congress—particularly their financial disclosure forms.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“Just the fact that this was available—this detailed genealogical data and these financial disclosures for members of Congress—allowed us to explore this link,” Sehgal says.

The racial wealth gap in the U.S. is staggering. More than one in five white households have a net worth of more than $1 million, whereas more than one in five Black households have zero or negative net worth. This extreme imbalance began with slavery and has been perpetuated by racist policies and practices in housing, education, hiring, voting, and more that prevent many Black Americans from attaining and passing on generational wealth.

“A lot of research [has looked] at descendants of enslaved people and less so at the people who benefited from slavery,” Sehgal says. Research published in 2020 by Robert Reece, a sociologist at the University of Texas at Austin, has shown that white people in counties with higher rates of slavery have better socioeconomic outcomes today. And a study of enslaver households found that although families who had enslaved nine or more people lost more wealth after the Civil War than those who enslaved fewer people, the grandsons of the enslavers had largely recovered their wealth by 1940. But researchers haven’t been able to trace those families’ outcomes to today because Census records after that point remain sealed.

The Reuters report allowed Sehgal and his co-author—his father, nephrologist Ashwini Sehgal of Case Western Reserve University—to create a far more detailed picture of how wealth created through forced labor still benefits enslavers’ descendants today.

“Being able to do this with individual people, with people who are still alive, is kind of remarkable,” says Reece, who was not involved in the new study. “It’s really one of the first studies of this type in the legacy of slavery research,” which itself is only about a decade old, he estimates.

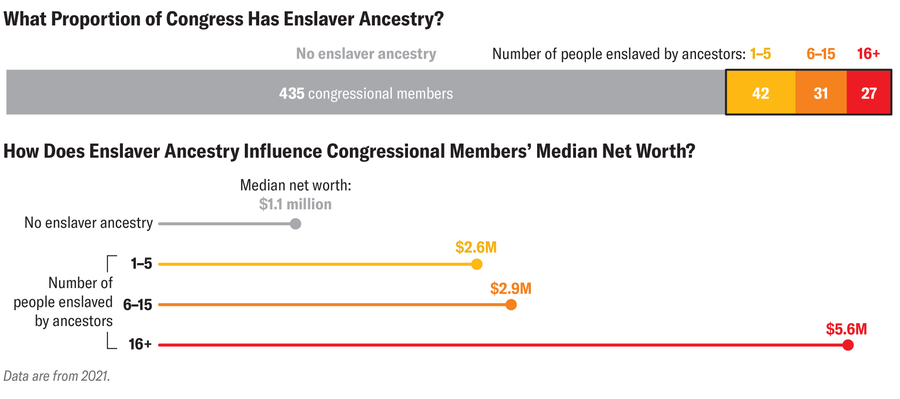

The Sehgals’ study matched each of the 535 congressional members who were in office (or whose vacant seat had not yet been filled) in April 2021 to their financial disclosure filings, which had been digitized by Business Insider. The researchers computed each member’s net worth by subtracting liabilities from assets. Next, they compared the median net worth between four groups: those whose ancestors enslaved zero people and those with forebears who enslaved between one and five, six and 15, or 16 or more people.

The more people the congressional members’ ancestors enslaved, the higher those lawmakers’ median net worth. This held true even after adjusting for age, race, sex, ethnicity and educational level. The group whose ancestors enslaved 16 or more people had a median net worth that was five times higher than the group with no enslaver ancestry—a difference of $3.93 million.

Amanda Montañez; Source: “Slaveholder Ancestry and Current Net Worth of Members of the United States Congress,” by Neil K. R. Sehgal and Ashwini R. Sehgal, in PLOS ONE. Published online August 21, 2024

The study shows how people “continue to benefit from this institution” of slavery, Reece says. “And I think that is a strong argument for things like racial reparations.”

The results likely underestimate the link between enslaver history and present-day wealth in Congress, Reece adds. The Reuters report only counted the number of people enslaved by the most recent enslaver in someone’s direct lineage, not the total number of people enslaved by all their direct ancestors. Also, someone could benefit from having an enslaver uncle, cousin or other nondirect ancestor, who would not have been counted in the analysis. Others’ ancestors may not have directly enslaved anyone but still been involved in industries that benefited from slavery. That includes the shipping industry, banks that issued loans to purchase enslaved people and companies that insured them, Reece says.

Additionally, members of Congress aren’t required to report federal retirement accounts or personal residences that do not generate income. Members are also allowed to report the worth of large assets in broad ranges that might underestimate their value.

These results are specific to Congress, a group that is not financially representative of the rest of the country. The legislators’ median net worth in 2021 was $1.28 million overall, far higher than that of the general population. The most recent Census surveys put median U.S. household wealth at $166,900—with a 10-fold-higher median for white households ($250,400) than Black households ($24,520).

“The overall result tracks with past research [on] how durable wealth is and how wealth perpetuates over time,” Neil K. R. Sehgal says. “People who were wealthier or more elite in the past, their offspring are still very wealthy and very elite.”

Conducting a similar study on the general population would be feasible but a heavy lift for researchers, requiring a larger sample size and therefore significantly more funding, Reece says. Still, the Congress-specific results are valuable in their own right for tracking the lasting impact of slavery on American wealth and politics. “That’s the population that runs the country,” Reece says. “If we were going to set aside any population to analyze in this way, I can’t think of a better one.”

Bills introducing reparations for slavery have stalled on the floors of the House of Representatives or the Senate for decades. One bill called House Resolution 40—named for the U.S. government’s unfulfilled 1865 promise that each adult man who had formerly been enslaved would get “40 acres and a mule”—has been introduced every year since 1989. Co-sponsored this year by 130 Democrats, this bill would create a commission to study and develop a reparations plan for Black Americans. It has never been brought to a vote.

Some lawmakers with family links to slavery have co-sponsored reparations bills in the House or Senate. They include Democratic Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, whose great-great-great-grandfather enslaved 14 people, and Democratic Representative Lloyd Doggett of Texas, whose great-great-great-great-grandfather enslaved three people.

“Though [this] discovery is troubling, it only invigorates my support for the cause of truth, justice and equity today,” Doggett told Reuters last year.

Republicans largely oppose the study or proposal of reparations. At a Trump rally in 2022, Republican Senator Tommy Tuberville of Alabama, whose great-great-great grandfather enslaved six people, equated people who would benefit from reparations with criminals. “They are not owed [reparations],” Tuberville said. He has a net worth of at least $4.5 million.